Different Tiles for Different Detail

When working from photos, it can be tempting

to take the easy way out: to simply create from a photo one large texture,

and wallpaper a large surface with it. There are however significant

disadvantages to this approach.

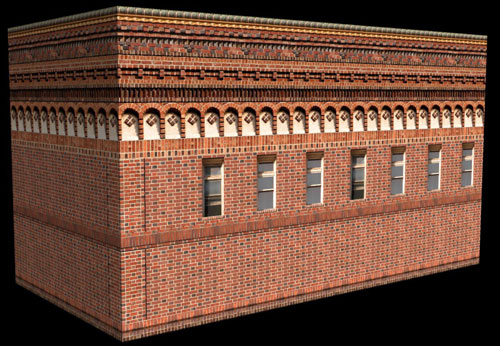

Consider the image below. This entire image tiles, so it is in fact

a tiling texture. A big one.

A texture like this is very easy to apply, and all of this

detail could be mapped onto one large quad. To match the texture

resolution we've been working with, this texture should be 1353x1216

pixels—double this if we wish to work at twice the resolution

of the required texture, as we have done so far. Of course, modern

digital cameras can capture images of this size. This represents

a rather large use of texture memory however.

It is wasteful,

because most of the detail in the image repeats horizontally

across the image. The basic brick pattern repeats vertically

as well. Smaller tiling textures could be made of each part.

There is also the disadvantage that this one large texture can

only be used to create this one wall, while isolating different

details to their own tiling textures allows for far greater flexibility.

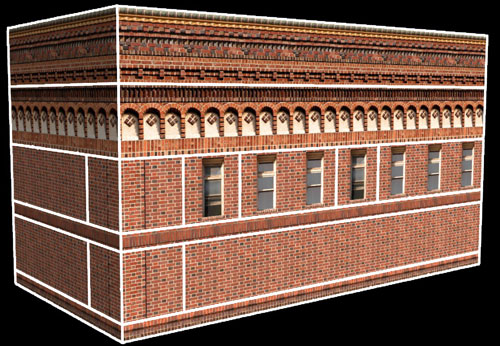

We can break this wall down into seven tiling textures. Adding

two end grain textures, we have a total of nine, two of which

are 256x64, for a resolution of fewer than 768 pixels square—a

substantial savings on texture space from the 1353x1216 pixels

required for the texture above (remember, I am working at a base

resolution of 512x512 with intent to scale down to 256x256).

These nine textures make up the walls below.

Notice the darker wall on the left above (darker because of

the lighting in the environment, not because of the textures

applied)—we already have available to us a simple variation

on the original wall that would not be available if we

used a single large texture.

Geometry for the bottom, middle, and top trim

has been provided. This is an effective way to vary the look

of surfaces textured with the same texture set. Trim textures

like this are often not square. The bottom and middle trim textures

shown above are 256x64. Resolutions of 256x32 or 256x128 are

not uncommon. In this case there are two top trim textures, each

256x256. This is probably less common.

In most game engines, a single quad can only have a single

texture map applied. Therefore the visible geometry cannot consist

of two large quads (one for each visible wall). More polygons will

be required for this texture set (that is, one quad will be required

for each separate texture that is applied). In the image below

the wireframe outline of the geometry is overlaid.

This is a

worthwhile tradeoff. Nineteen quads is not a lot for a modern

game engine. It is simple enough to vary the dimensions of the

geometry in order to accommodate trim textures of different resolutions,

and different building shapes and sizes.

It

is worth noting that in many cases a level designer may be building

the geometry, not the texture artist. The designer is likely

however to understand the ways that textures and texture sets

will dictate the way the geometry is built.

|

Here I've superimposed lines over my test geometry

so you can see exactly how the tiles were arranged. |

Expanding the Possibilities

By expanding the set we begin to increase the possibilities.

Adding three more textures, and using the same geometry, we can

create a different building in the same style, perhaps located in the

same complex as the building above.

A few more textures and a slight change in geometry offer

us another very different look to the top detailing of the building.

Windows are of course an important and distinctive feature.

If we expand the set just a little further, we can begin to mix

and match the various parts.

With the addition of the nine textures above, we can create

a great many wall variations. Some of the possibilities are shown

below.

When Is Your Texture Set Complete?

This building is going to need a door. Most likely, your set

should include several doors. There will normally be grand doors,

for main entrances to the building, and more simple back or side

doors.

You'll probably always find that as you begin to create geometry

and apply textures you discover that more textures are needed.

As an artist you will normally work closely with a designer who

will apply your textures to an environment. You will need to

try to anticipate the needs of the environment your designer

is building. There will be textures in your set that the designer

never uses, and there will be new textures that he or she requests

along the way.

When I was working on Akuji the Heartless for the PlayStation,

I worked closely with the level designer, and often made textures

on request. I made one texture to be used on a ship, above the

deck, on the walls that prevent the sailors from sliding off

into the ocean (in some places there were railings, and in other

places walls, the tops of which were probably just above waist

height). It showed the same planks that were on the hull of the

ship, but with large struts to create a more realistic look.

The designer immediately found a dozen uses for that texture

that I had never thought of—walls inside of rooms, ceilings,

the back side of almost any wooden surface. The number of uses

for that texture expanded to a dozen and one when I showed him

where I had intended the texture to be used!

Your texture set will thus often be complete only when the

environment itself is complete. Even then, you may work on later levels

in the game or its sequel, so you may well find a later use for textures you have made or discarded in your project.

Lighting is already "built in" to most of the textures

in our set so far. Lighting is often an important part of the

illusion. It contributes to the impression that the texture

has some depth, as opposed to being the completely flat computer-generated surface that it

actually is.

|

| UT2004 features highly detailed environments and

models, however sometimes detail is still added via textures rather

than geometry. Note the horizontal concrete beams in the image above:

the shadow under the top edge and the highlight above the bottom

ledge give the appearance of more detail than is actually there.

The same is true of the metal I-beams above. If you look at the edges

of the beams (for example, where the I-beams meet the walls), you

should be able to see where the illusion breaks down. Click to enlarge. |

|

The same effect is at work on the support beams

shown here. Click to enlarge. |

Consider the textures below. Some parts are lit, others are

in shadow. Even the ground texture below includes shadows cast

by one surface onto another surface.

These shadows come from the original photographs. They can

sometimes be too real. You will often have virtual lights in

your game environments, and these lights will cast shadows. It

can sometimes be very obvious if the shadows in your textures

fall in a different direction than the shadows cast by objects

in the environment. At the very least, you will want to be sure

that the shadows in your set all fall the same way. Do you notice

any inconsistency in the textures above? Perhaps you didn't

notice this until I pointed it out. This is one indication of what

you can get away with.

Ideally, anything that casts shadows will be geometry—all of your windows will be inset slightly from the walls, for example, and

the window ledges will protrude slightly. As the power of game

systems increases, the number of polygons that can be drawn increases, allowing much

more detailed models to be created. This

allows more and more of the lighting and shadows to be left to

actual lights in the game, rather than simulating the effect by painting it into textures.

In some cases, you may want to include lighting in your texture that

is emitted by objects represented in the texture. The example below is

from a hypothetical "moonless night" version of our texture

set, to emphasize the point.

|

Here light is emitted

by the lamp in the texture image, not the actual lights in the

game. |

Light Maps

Most modern game engines can use light

maps. Light maps are created by pre-rendering

the lighting of the environment, and storing the lighting information

in a large map that is applied by the game engine at render time. Light

maps are often the most effective way to add lighting to textures,

and you should usually use them when available, rather than add lighting

to your textures as in the example above. Light maps will be explained

in more detail in the next lecture.

Bump Maps

Another option involves working your textures

to make the lighting more generic. You can create textures that don't

include

such strong shadows, and thus don't give an indication as to which

way the light is hitting them. Sometimes a texture is painted

so that the parts that protrude, that are closer to you, are lighter,

and the parts that are recessed are darker. This is also a simple

description of how bump maps are made...

Bump maps are image maps separate from

texture maps that can be used by some game engines to further create

the illusion of

a 3D surface. The trick is done in the lighting; when the surface

is rendered, the surface is shaded, using the bump map, as if

bumps were present on the surface. The name is descriptive in

that bump maps can add bumps to the surface, but not great depth. A brick

texture is a good example of one that might have a bump map. Accompanying

the brick texture would be a black and white image that shows what areas

should appear to protrude (the bricks) and what areas should appear to

recede (the mortar). We'll explore this idea more in Lecture

Six.