In graphic design as we know it, all of our work is contained in a digital environment. Even if you do an entire poster by hand, building type and image with collage and paint, you'll need to digitize everything in order to get it printed.

|

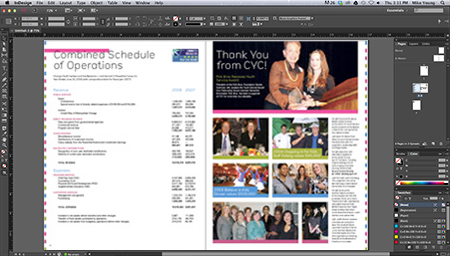

A print design in its digital home, InDesign |

Thus, it's really important to understand how your computer captures, creates, and interprets your design. This understanding will support your use of software to carry out different tasks.

You wouldn't use Illustrator to create book layouts any more than you would use InDesign to do photo editing. These programs have been developed for over a decade to handle very specific tasks.

There is a lot of overlap in tasks though, which can be very convenient but also kind of misleading. For example, Photoshop, Illustrator, and InDesign each allow you to play with layering and transparency options such as Multiply or Overlay. Tools like this give you a lot of streamlined creative control. But you must be smart about over-building image layers in InDesign when it may be smarter to do this in Photoshop. Simple, right?

With the Creative Cloud concept, Adobe has made it a point to recognize that all of these programs are necessary to the design process individually, but in the end, all of the formats must understand how to merge with one another in some way.

Thanks to Adobe's clever engineering, you can copy Illustrator drawings into Photoshop, place JPEGs into Illustrator, and place just about any kind of image into InDesign amidst hundreds of pages of well-managed text. However, with great power comes great responsibility. Just because InDesign will allow you to place a web-sized JPEG or PNG into a print brochure doesn't mean it's a smart idea.

Computers and software are pretty brilliant these days, but they're not built with common sense. This is where you come in.

Vector and Raster: The Yin and Yang of Design Files

The simplest way to define an image file is to first consider if it's vector or raster. Let's take a moment for a quick refresher of these two file types and how they relate to print.

|

A vector file defined by paths |

A vector file is a collection of mathematic equations that the computer uses to define Bezier curves (from the Pen tool), circles and squares, outlined type, and all those great paths and fills that you create in Illustrator and InDesign. The computer understands the shapes and remembers where they go and how they interact.

The beauty of a vector file is that it has no need for resolution. A vector logo drawn in Illustrator can be scaled down to the size of a dime, then scaled up to the size of a continent, and it will never lose image quality or become pixelated. This is because the image doesn't really contain pixels. It's just an idea that the computer translates into pixels so you can see it on the screen.

|

The all-too-familiar pixels that make up raster files |

A raster file (or bitmap), however, is constructed in pixels. If you take a 3" x 3" image at 72 ppi (web resolution, remember?) and print it out at 3" x 3" on paper, it's going to look terrible. Similarly, if you have an image of the same size at a decent print resolution and scale it to the size of a billboard, it will look incredibly ragged.

Each file type has its own pros and cons. For example, pixels do a much better job of simulating a printed photograph because they allow for the minute variations in tone and contrast that make up a photographic image. Vector shapes are much more suited for hard edges, things like logos and typography.

Now that we have a formal way of organizing our file types, let's take a look at the software we use to manipulate these files, in the context of the production process.

Adobe InDesign: The Silent Genius

No matter what you're designing for print, odds are the project is going to end up in InDesign. It's not always necessary, but it sure is the smartest way to approach anything in print design. (A quick note: I recognize that QuarkXPress is still in use for some in the publishing industry, but I haven't used QuarkXPress, or met many who use it, since I started my career in print design.)

InDesign's magic is in handling multiple pages of text, raster photos, vector drawings... well, just about anything you can throw in there. It's a fantastic catch-all for your project—the place where you can collect and manage all items of a print project. It's especially adept at handling large amounts of text in ways that Photoshop and Illustrator can't come close to.

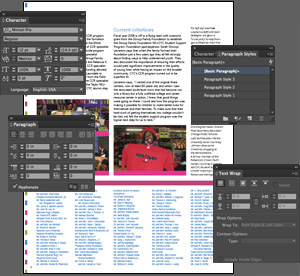

|

InDesign and a few of the many panels that handle text |

Its power is in its role as a link between the designer and the prepress crew at a print shop. InDesign allows you to see swatches, color mixes, ink settings, and tons of other options that a prepress specialist will be using to get your job ready for print.

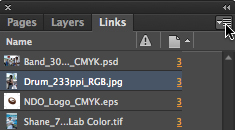

The file type associated with InDesign is INDD (extension .indd). An important thing to remember about INDD files is that they don't actually hold that much information. The only content that an InDesign file actually holds is text, formatting, and the location of graphic elements. Everything else you see in an InDesign file is "linked." That is, InDesign remembers where your images, logos, and other files are, understands how they interact with other images and text, and knows where they are on your computer. But these images don't actually exist inside the file anywhere.

The file type associated with InDesign is INDD (extension .indd). An important thing to remember about INDD files is that they don't actually hold that much information. The only content that an InDesign file actually holds is text, formatting, and the location of graphic elements. Everything else you see in an InDesign file is "linked." That is, InDesign remembers where your images, logos, and other files are, understands how they interact with other images and text, and knows where they are on your computer. But these images don't actually exist inside the file anywhere.

(InDesign will allow you to "embed" your images in the document, but there's not really a need to do this. It will only increase your file size and limit your ability to live edit the image.)

Another important thing to remember about INDD files: if you save an INDD file in a newer version of InDesign, such as CC, and try to open it in an older version, such as CS6, it won't open. In these cases, save your file as an IDML instead.

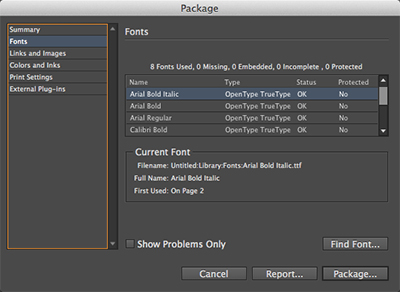

When you send a file to print, you will use the Package option in InDesign (File > Package), which copies and collects all of your linked files into a file folder for you. The intent here is to create a package, a self-contained file folder that you can send to your printer. This will contain every possible item needed to run the job successfully, meaning the InDesign file and its linked files.

|

| The Package option in InDesign will provide you with an overview of the files and settings in your document and will alert you to any issues such as missing fonts and images. |

The package will also contain all font files used in your design. The prepress folks will use these fonts on their machines to ensure that no confusion is created between your version of a font and theirs. Otherwise all of your careful typesetting could be absolutely slaughtered.

Another option with InDesign—and this is a big deal these days—is its ability to export to PDF (File > Export). Adobe's PDF, or Portable Document Format, is a fantastic tool for ensuring that any computer, using any operating system, regardless of its available fonts, can open and read a file and see it as it was intended. The elements of a PDF are locked into place and cannot be edited in a PDF reader. This is a great way to ensure that no information in your design is lost, altered, or corrupted. It's not perfect in this respect, but it does extremely well.

A PDF file can contain both vector and raster information across multiple pages and can be used for screen-quality viewing in a file size small enough to email. It can also be used to deliver a high-resolution print ad—full of clean text and the richest photography—at a file size that is large but a resolution plenty high enough for the most upscale magazine.

Adobe Photoshop: The Raster Master

Photoshop, of course, is your go-to for editing all aspects of raster files. It's also quite smart these days when it comes to handling and manipulating vector objects, which it stores in layers until they are converted to pixels.

From a production perspective, you should use Photoshop to resize files, adjust resolution, do color correction, retouch problem areas, and change color mode when needed from RGB to CMYK or grayscale.

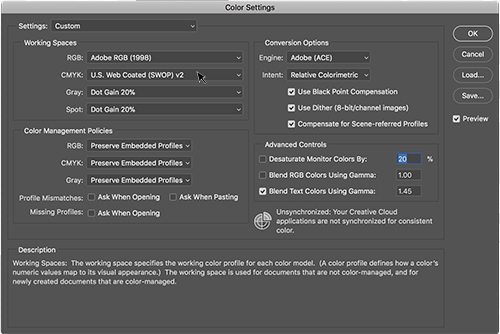

|

You can adjust Color Settings in Photoshop (Edit > Color Settings) and other Creative Cloud applications for the type of paper you plan to use. |

Whenever possible, save any raster files handled in Photoshop as layered, high-resolution file types like PSD or TIFF. Saving files in JPEG format, even as high-res JPEGs, causes information loss with every save, which is an advantage for web use, but a disadvantage in print. PSDs and TIFFs are non-lossy, so convert to one of these whenever possible. I personally prefer layered PSDs because they are Photoshop-specific and more natural to the Creative Cloud/Suite concept.

Photoshop can open nearly all file types, including some vector files. But don't be misled by this, or get fooled into thinking it's a good idea to work on an Illustrator EPS in Photoshop! Remember the software's intent...it does best with rasters.

Adobe Illustrator: The Vector Inspector

Illustrator is a software environment designed to create and manipulate vector shapes. It can be used for layout, especially in situations where there are more graphic elements than text, though I personally prefer to do anything that will print in InDesign.

Common examples of Illustrator projects are logos and business cards, as you might expect. And because of the multiple artboards feature, you can simulate a multiple-page document with artboards. I've seen this used to handle the various sides of a cat litter bag, for instance, with different artboards used to cover the different panels of the bag. This was provided to a printer as print-ready art, but I would never recommend this personally.

|

You can choose the number of artboards in Illustrator's New Document dialog, however Illustrator is not recommended for multi-page documents. |

The most common vector file you'll receive or create for use in a print document is a logo. However, you can expect to eventually come across things like architectural renderings, city maps, and myriad other situations in which straight lines, hard shapes, type, and color fields are the main event.

Illustrator does best with AI, EPS, or PDF, all of which will give varying levels of editability.

Now you have a good sense of where the Adobe trifecta comes into play. Let's try to put it into context with an example project. Click here to grab the Lecture Two download files and follow along. You can also find the Lecture Two downloads in the Course Downloads area.

Here's the situation: your client at NDO gets in touch, you determine a project to move forward with (an 8.5" x 11" event flyer for an upcoming show), and then everything is all set to move forward. He sends you a Microsoft Word file, an EPS logo, and three photographs of varying format, resolution, size, and color space. You know you'll need to get all this in a form that will print at a great quality, at the scale of a small flyer. We'll do this by packing it all into InDesign and sending it to print.

But first you'll need to look at all the files and make sure they're in good shape. Organize your files on your hard drive, putting them in a centralized location. (Not your desktop!) More often than not, the best way to do this is create a "job folder" that contains all the necessary files for any given project.

|

The job folder should contain everything given to you by the client. |

Early in the process, develop a system of subfolders for your job folder. For example, "Images," "Sketches," "For Print," "From Client," and "Client PDFs" could be good starters. You should develop a system that works best with your workflow, but the point is to keep everything clean and neat. Otherwise, your job folder will turn into a total mess, which will slow you down in the end.

Now, for the individual files. Check them one by one to see what's needed and make changes as appropriate. Start by opening up the logo in Illustrator, because EPS is a vector file format. Make sure that the file isn't corrupt, that the color space is appropriate, and resave if necessary. The color space you should be working in right now is RGB so we can convert everything to CMYK in one fell swoop at the end.

Now, for the individual files. Check them one by one to see what's needed and make changes as appropriate. Start by opening up the logo in Illustrator, because EPS is a vector file format. Make sure that the file isn't corrupt, that the color space is appropriate, and resave if necessary. The color space you should be working in right now is RGB so we can convert everything to CMYK in one fell swoop at the end.

Repeat the process with the image files. Check the size and resolution of each one (Image > Image Size) and the color space (Image > Mode). You'll want 300 ppi images in RGB mode, sized appropriately for an 8.5" x 11" event flyer.

Keep in mind that if you receive small or low-res images, scaling up to large dimensions will degrade the quality. You'll have to make some design judgment calls... should you use the images at all? Can you use them at a small size as an intentional part of the design? Save your converted images to PSD.

In a real world project, you'll probably have a few rounds of changes to make to these photos, so my recommendation is to keep them in RGB format until your whole design is just about ready to go to print. When you're sure you won't make any more changes, use Image > Mode and convert to CMYK.

Open up the Word DOC, copy the text, and paste it into InDesign. Be aware that any bold, italic, underlining, or other text styling will be lost or possibly broken in this copy and paste! Even if InDesign preserves styling from a Word DOC, it's always a good idea to strip it and build your own styles in InDesign.

Once your text is copied and styled to your liking, you can begin to import your images into InDesign. This isn't a copy/paste of images and graphics. And it's not an embedding of images, like you may have done in Illustrator for previous projects. This is File > Place in InDesign, which creates a link to the file as it exists on your hard drive. We'll revisit this process in more detail later in the course.

From here on, it's just a matter of working your design magic. Any editing that happens to your images (such as in Photoshop) will be reflected automatically or once you update your links in InDesign. Try it out! Select one of the images in the Links panel (Window > Links), then click the flyout menu icon in the upper right of the panel and choose Edit With > Adobe Photoshop.

From here on, it's just a matter of working your design magic. Any editing that happens to your images (such as in Photoshop) will be reflected automatically or once you update your links in InDesign. Try it out! Select one of the images in the Links panel (Window > Links), then click the flyout menu icon in the upper right of the panel and choose Edit With > Adobe Photoshop.

Make a change to this image in Photoshop (for example, desaturate it or adjust its levels). Save the changed file, then go back to InDesign. If you see the change immediately, you're all set! If not, go back to the Links flyout menu and choose Update Link (or Relink if you've saved the file under a different name).

Take a few moments to keep playing with the files in InDesign, Photoshop, and Illustrator and think about how you would turn these into an attractive, cohesive design. Save an INDD file to use in the next step.

If this really were your client, you would save different versions of your design if necessary, and when the job is ready, send it off for client approval. Once he gives the thumbs up, you can get ready to deliver your files to the printer. There are a few ways of doing this.

Delivering Your Files

With your INDD file for the flyer ready, package it up in InDesign (File > Package). Review each part of the dialog for any warnings such as broken image links (which might occur if you move a file) or missing fonts. We'll talk more about packaging later in the course, but for now your work with the flyer is complete. Nice job! Now imagine that you're ready to get this package to the printer.

Once you have used InDesign's package feature, it's time to archive or ZIP the package folder and send it to your printer.

This can be done in a variety of ways, and the best way for any job depends on the printer's preferences and the file size you're dealing with. Often enough, a zipped file is small enough to be sent via email. And of course, any printer will accept a USB flash drive with all of the appropriate files. You can get a flash drive that can store up to 256 gigabytes.

In some cases, when shipping a flash drive doesn't make sense, you may need to use a variety of web-based file transfers.

|

|

|

| |

-

Google Drive: You can transfer up to 15 gigabytes free using Google's cloud sharing service. Link

-

Dropbox: Another web-based file transfer service that allows you to upload at least 2 gigabytes of files free of charge. Link

-

FTP: Stands for file transfer protocol. This method is a bit dated and complex in that you need software, often free, to log in and enter a password to complete the transfer. You would also need a web host server to move the files to where the second party could download from.

-

Peer-to-peer: A network that connects online companions, or peers.

-

Third-party transfer sites: There are many sites available you can use to transfer large files. Sizes and costs vary among them.

|

|

|

|

|

As an alternative, many commercial printers have moved to a simple web page upload tool that simplifies the process to about two steps and requires no special software and minimal savvy. In the end, you will need to work with your printer to determine the fastest and most reliable solution for sending your files.

You know the next step...get that project printed! We've already talked about how offset litho works in the last lecture, but that isn't the only print method out there. It just happens to be the most accessible.

Let's take a brief look at some other options, which you may or may not encounter in your entire design career. In the end, these likely won't need any print production processes other than those you've learned here. But they are important to know because they often impact the budget of your job in a big way, when the need arises.

Offset Web Press

An offset web press is simply an offset litho press that feeds the paper from a giant roll, rather than sheet-by-sheet. This allows things to go much more quickly when larger volumes are being printed, such as coupons destined for a national newspaper. Offset web is great for print jobs like this, where quality falls a bit, but quantity and speed are more important. We're talking quantities in the tens or hundreds of thousands. This is a situation where offset web is superior to offset litho.

The offset litho press previously discussed is known in the industry as "sheetfed" as opposed to "web." Most offset jobs will be run on a sheetfed press. Assume offset litho when the term "offset" comes up unless offset web or digital offset are specified.

Digital Offset

Digital offset is a broad term for a somewhat recent development in commercial printing. The gist of this technology is that printing companies have taken familiar forms like color laser printing and inkjet printing and developed them into high-quality, higher-volume printers known as digital presses. They operate on the same basis as their household equivalents, but they are the size of a car and perform much more beautifully than your desktop printer would.

There seem to be two major technologies behind digital presses: digital offset presses and toner-based presses. In my experience, the dominant manufacturers for these machines are HP and Xerox, respectively. HP's Indigo Press is a digital offset press with some amazing technology behind it. It uses inks that are much more fluid than those for a traditional offset press. In fact, they are more similar to the inks of an inkjet printer. The accuracy of an Indigo press is now "dot for dot" like the quality of a traditional offset press. That is, the Indigo reproduces the same kind of dot patterns that an offset litho would, presenting a remarkably similar color quality, ink density, and level of detail.

|

An HP Indigo digital press |

The advantage, of course, is that digital presses can generate and modify their printing surfaces on the fly by altering the image on their electrically charged rollers. These rollers replace the burned screen and blanket rollers of a litho press. Because the Indigo (for example) requires no physical offset screens or manual setup, the setup costs are much lower.

Digital offset is great for small runs of items—in the realm of 50-1,000 items—because there is no need for burning plates or prepping the offset press. This makes the job quicker, less expensive, and ideal for situations where something in the design, such as a personalized address, needs to change with every item. There is typically a quantity of items where, when deciding to go with digital or offset, you will see a price break. That is, due to the setup and operation costs of a particular press, the price per unit will see a dramatic shift.

Digital offset's available print size is always smaller than an offset press sheet. For instance, digital offset printing options are limited to a print area of 11" x 17". In toner-based digital presses, which are more or less giant color Xerox machines, the press sheet may be closer to that of an offset press. There is no standard to speak of in digital offset, so check with your printer to see what he has to offer.

Gravure

Rotogravure, or gravure for short, involves engraving the image onto a copper cylinder and rotating it against long reels of paper that are later trimmed to size. It is a rotary printing press like offset litho. However, its uses are wider-ranging than offset, especially where high quantity, quality, and tremendous speed are an absolute necessity. This is the case with mass-produced magazines, corrugated cardboard packaging, and specialty processes like vinyl flooring. Gravure is the fastest and widest kind of press available.

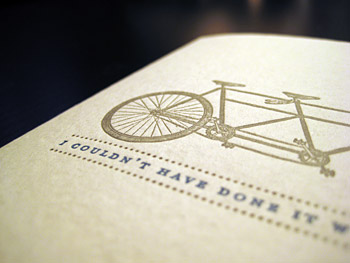

Letterpress

Letterpress, the oldest form of printing, applies a solid plate with letters and images pressed to paper. The area that prints is raised above the non-printed areas. This is the very same method that Gutenberg perfected. It is a very rare process today, but a beautiful form of printing that is kept alive by typographers and printers who embrace and appreciate this timeless craft.

|

Letterpress has a lovely old-time feel, and is making a comeback for greeting cards and invitations. |

Using the same principles as the letterpress process, flexography involves the application of a flexible surface to uneven surfaces such as cardboard, cans, coffee mugs, and so on.

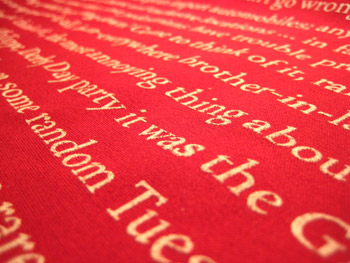

Screen Printing

Also known as silk-screen printing, screen printing uses a fine mesh of stainless steel or fabric (at one time using actual silk, but now a cheaper synthetic fabric that emulates silk is widely used). The screen is mounted on a frame and non-print areas of the screen are blocked out with a stencil. A squeegee is used to force the ink through the open areas of the stencil. It can be used on cotton tee shirts and other fabrics, banners, posters, and more, but it is generally reserved for continuous tone images such as logos, text, and images of solid color.

|

Screen printing on fabric |