The Time Capsule Test

Before we begin, here's a brain teaser. In this lecture, I will discuss why great art often reveals an aspect of society. How do we know whether art has something important to say about its time?

When I am viewing a work of art that shows a slice of society (present or past), I always play a little game or test on it.

I ask myself: If I were to send this piece of art into outer space, for an alien creature to learn something about humanity, what would this piece say? What would the aliens think about us? Would they be attracted or repulsed by the art? Would they plan to visit Earth, or head off into some other solar system?

This test, silly as may seem, helps me understand the content of the work, which I might otherwise take for granted. I invite you to do the same each time you appreciate a piece of art work! You will see that even the plainest picture can give us a tremendous amount to think about.

Now, let's revisit the Baroque era...

In the last lecture, we learned that Baroque art was strongly influenced by its historical context. In the Baroque era, artists began to explore social themes as a reaction to the idealization of reality in Renaissance art.

It was an exciting time. Artists began to open their eyes and use their surroundings as subject matter. They were convinced that if they represented the events of the everyday world, the themes they depicted would be appreciated for generations to come.

Dutch Baroque Artists

Frans Hals (1582-1666) was a Dutch artist who painted with bold, broad brushstrokes. He is well-known for his excellent portraiture. Hals painted group portraits of civic guards (social organizations for men) and leaders of social welfare organizations. One of these paintings is Banquet of Officers of the Civic Guard of Saint George at Haarlem (1616). Another is The Women Regents of the Old Men's Home at Haarlem (1664), an institution where Hals spent his final years.

|

The Fool or Jester with a Lute (1620-1625) - Frans Hals. Hals also depicted popular characters of his time such us jugglers, musicians, and drunkards.

|

Jan Steen (1626-1679), also Dutch, painted many lively and humorous works celebrating everyday events such as schoolroom activities, festive customs, and holiday celebrations. Steen's colorful compositions are crowded with people of all ages, laughing, drinking, eating, playing games, and dancing. Steen was an innkeeper by trade, which perhaps explains his keen insight into casual human behavior. In the painting Eve of St. Nicholas (1660), he depicts a family gathering enjoying the Christmas season. He also painted works based on popular proverbs, inscribing them clearly in his paintings in an attempt to teach moral lessons.

In contrast to Steen, Dutchman Jan Vermeer (1632-1675) created paintings without any clear moral or dramatic narrative. Vermeer's works showed single figures, generally women, engaged in simple everyday tasks in a domestic

interior setting. Vermeer's compositions were very simple but beautiful; everyday activities shine with an intimate splendor. Vermeer left no more than 35 pictures in all, but through them we can understand a lot about Dutch society at the time.

Most of his female subjects are portrayed near a window, in between the privacy of their home and the public sphere of the street. With this simple symbol (the window), he differentiates the private from the public. Subtly, he also highlights the changing role of women in 17th century Dutch society, a transition from mainly doing household activities to undertaking a more public role.

|

The Milkmaid (1658-1660) - Jan Vermeer. In this painting, Vermeer depicts a maid fixing breakfast. The meticulous detail creates a feeling of intimacy. The window is symbolic of the changing role of women as well as illuminating the composition.

|

Judith Leyster (1609-1690), like Vermeer, specialized in understated scenes of everyday life, but she also painted outrageous scenes of tavern life. In The Last Drop (1628) two young men are shown drinking and smoking. A skeleton crouches behind them, reminding us of the passage of time and what lies ahead for these men if they keep on with that behavior.

Rococo was a cousin of Baroque, and the painting style can seem very similar, however the themes (and hence the tone and drama of recoco painting) are quite different.

The Rococo style developed in France after the death of Louis XIV in 1715. Rococo artists depicted aristocratic decadence and the birth of bourgeoisie, the French middle class. The paintings were an expression of wit and frivolity, with a satirical undercurrent. Though much Rococo art appears to depict a world of fantasy and grace, it includes an underlying emphasis on facts and is highly symbolic. An ironic tone implies an awareness of the state of corruption and triviality into which European society was falling.

Though most Rococo painting and architecture is frilly, exaggerated, dense in a decorative way, and somehow artificial, some artists were

severe social critics in this pretentious style.

Differing Approaches to Rococo

Antoine Watteau (1684-1721), a French painter, developed a style called fete galante, in which artists created paintings of festive outdoor gatherings where elegant aristocrats relaxed and practiced courtship. In his work, Pilgrimage to Cythera (1717), he depicts a group of couples preparing to depart the magical island of Venus. As they begin their return to the world of reality, their costumes become dull and colorless, reflecting a mood of melancholy.

|

Pilgrimage to Cythera - Antoine Watteau. Note the difference between the Rococo and the Baroque painters in their treatment of people. Watteau's thin and graceful proportions are typical of the Rococo style. He emphasizes silks and other textures that reflect light.

|

William Hogarth (1697-1764) was the leading satirical painter of the 1700s and a noted engraver. His pictures humorously commented on the manners and morals of his time. In Marriage a la Mode (1745), he makes fun of hypocritical commitments to the marriage contract. A young wife is almost caught being unfaithful with a music teacher, who tries to pull up his pants in the next room. The husband himself seems to have indulged in some impropriety of his own as he bears the

black mark of syphilis on his neck.

|

Marriage a la Mode, Scene 2 of 6 (1743-1745) - William Hogarth. In Hogarth's image, cynicism rules. Take a moment to check out the facial expressions of the characters...what would an alien think?! This painting reflects a frivolous lifestyle.

|

Unlike French contemporaries Watteau or Jean Honoré Fragonard (another Rococo painter), Jean-Baptiste Chardin (1699-1779) used still life and everyday life scenes instead of aristocratic elegance as his subject matter. His work is associated with a trend called bourgeois chardin. His careful application of color gives his paintings a smooth and delicate quality. In Pipe and Jug (undated) the objects seem to be arranged by a person who might return at any

moment. He implies a human presence even though he eliminates people from the picture.

Slightly later in the Rococo movement, Benjamin West (1738-1820) became famous for his large pictures of historical subjects. Though he settled in London, West painted important moments in American history like The Death of General Wolfe (1770) and Penn's Treaty with the Indians. Oddly, West decided to dress his subjects in a contemporary manner.

Romanticism began in the late 18th century as a reaction, in the name of reason and nature, to the artificiality of rococo art. The Romantics had an idealistic nostalgia for the past, and a desire to express an individual's innermost beliefs, feelings, or emotions. They were also advocates for returning to nature—hence many Romantics were landscapers (planners of parks and gardens) as well as artists.

Though most Romantic artists were detached from contemporary life—off painting faraway, exotic, and emotional subjects—some were deeply rooted in reality and felt a responsibility to respond to the events of the

day in their work. Let's meet some of those responsible Romantics now.

Social Commentary Through Romanticism

The French painter Eugene Delacroix (1789-1863) expressed his sympathy for the Greeks' struggle for independence from Turkey in his

work The Massacre at Chios (1824).

|

Greece Expiring on the Ruins of Missolonghi (1852) - Eugene Delacroix. By representing Greece as a young woman, Delacroix makes a commentary about women's role in the country's struggle for independence, in which men and women fought shoulder to shoulder against the Turkish domination.

|

In 1830, Delacroix took part in a revolution in Paris that freed France from an absolute monarchy. His painting Liberty Leading the People (1830) exalts this event. His celebrated journal or diary is a useful source of information on the social context of his life, as well as on his philosophy of art.

Theodore Géricault (1791-1824) was a painter whose commitment to social justice was reflected in his work The Raft of the Medusa (1819). In this painting, he commented on a contemporary shipwreck of the frigate Medusa. The captain, officers, and some of the passengers boarded six lifeboats, leaving the 149 remaining passengers crammed adrift on a wooden raft. Only 15 people survived. Géricault was also interested in human psychology. He created many pictures of insane people, such as Madwoman with a Mania of Envy (1822) and The Madman (1821). He had great sympathy for his subjects, treating them as fellow humans instead of outcasts.

The Spanish painter Francisco Goya (1746-1828) displayed throughout his work his support for the causes of intellectual and political freedom. He mixed educational and social messages in his etching series Los Caprichos (1799). In his painting The Executions of the Third of May, 1808 (1814), he depicted the massacre committed by the French army in Madrid and other Spanish towns after two Spanish rebels fired on fifteen soldiers of Napoleon's army. The French killed over 1,000 Spaniards in retaliation. By dramatically juxtaposing the visible faces of the victims with the covered faces of the executioners, Goya champions Enlightenment views of individual freedom against political oppression.

|

The Executions of the Third of May (1814) - Francisco Goya. The main character in the painting is the man with the white shirt, depicted in a Christ-like pose. Goya sheds a special kind of light over him to emphasize the importance of his sacrifice. The thick brush strokes accentuate the emotional poses and gestures.

|

The term realism was coined in 1840, but the style of art and the concept began to flourish well before that time. Realism as an art movement began as a reaction to neo-classicism and the romantic idealization of life. The Realists tried to be as objective in their art as possible—their primary concerns were to observe society and nature as faithfully as possible, and to engage in political and social satire. This was a natural outgrowth of an increasing awareness of social injustice at the time.

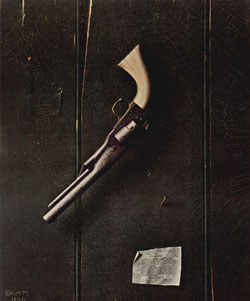

|

Colt (1890) - William Harnett. Harnett depicts with extreme realism this gun hanging from a nail in the wall. The image has a certain domesticity to it, as if the gun is just another everyday household item.

|

Commentary and Controversy in RealisticPainting

The French painter Honoré Daumier (1808-1879) was one of the most direct commentators on social injustice. He worked mainly in lithography, which made him an excellent cartoonist, but he also painted and made sculptures.

Daumier's work ranged from light satire to grim realism. Many of his caricatures ridiculed middle-class tastes and values. He satirized lawyers, doctors, businessmen, actors and even the king himself, in Louis Phillipe as Gargantua (1831). In the painting, he depicted the king as gigantic and monster-like, devouring taxes: the last coins of a group of ragged people. Daumier was also an advocate for freedom of the press, which he supported in his painting The Freedom of the Press: Don't Meddle with It (1834).

Painter Gustave Courbet (1819-1877), also French, supported the revolution of 1848. He created great controversy when he showed his two most important paintings of rural society: A Burial at Ornans and The Stonebreakers. At the time, peasants were becoming a strong political force, and Courbet's portrayal of this new force disturbed his conservative critics. In The Stonebreakers (1849) he depicted the mindless, repetitive nature of physical labor in poverty.

|

Burial at Ornans (1849-1850) - Gustave Courbet. You can feel an intense Catholic fervor in this compact group of people. The minimal variety in the image reflects the monotonous reality of rural life in the XIX century France.

|

Jean Francois Millet (1814-1875) also made powerful paintings of French rural labor. In fact, he and Courbet were suspected of harboring anarchistic views. In his oil painting, The Gleaners (1857) he depicted three women picking up the leftovers of the harvest, gathering wheat in their skirts. In contrast is the prosperous farm in the background. This painting inspired a wonderful movie by the contemporary French filmmaker Agnes Vardá, Le Glaneurs et Le Glaneuse. It's worth checking it out!

|

The Shepherdess: Plains of Barbizon (1862) - Jean Francois Millet. Millet portrays this young laborer with delicacy. While her attitude is modest, the size of the flock suggests that she works hard and has great responsibility.

|

In America, Thomas Eakins (1844-1916) created a landmark in painting in a work called The Gross Clinic (1875-1876). In the painting, he depicts an anatomy class lead by Doctor Samuel Gross in which a team of surgeons performed an operation in front of an audience in an amphitheater. This kind of "live action" painting is precursor of the role that photography began to play in the late 1800s.

Eakins also painted portraits and many outdoor settings and sporting events. He tried to achieve scientific accuracy and painstaking detail without losing emotion in his work.

|

The Gross Clinic (1875) - Thomas Eakins. Eakins uses atmospheric perspective to highlight the surgical procedure in the foreground. The main character is distinguished by a strong point of light that hits his forehead.

|

Photography

In the late 19th century, at the same time as painting was becoming more realistic, photography was becoming an art form in its own right. Photography was of course objective by its very nature. It became very popular and its potential for portraiture and journalism was widely recognized.

The appearance of photography as a method creative expression was in many ways a catalyst for the development of modern painting. Painters didn't need to copy nature anymore, as photography could really "capture" a moment in time. The camera could do the painter's job. That is when artists started experimenting with color and light, shapes and distortion, and major modern styles

such as Impressionism began to develop.

|

L'Atelier l'Artiste (The Artist's Studio) (1837) - Louis J. M. Daguerre. Daguerre developed an early photographic process using an iodine-sensitive silver plate and mercury vapor that was named daguerrotype after him. In this still life he uses light and shadow in a dramatic way.

|

Creative Photographers

The French Gaspard-Felix Tournacho, best known as Nadar (1820-1910) is one of the best photographers of all time. This is appropriate because Tournacho was the first one to use the medium in a creative way. His portraits provided a remarkable insight into the subject's personality and profession through their emphasis on pose and gesture.

In 1864, Tournacho took a wonderful portrait of the actress Sarah Bernhardt, in which he illustrated the possibilities of subtle tone gradation in the photographic medium. He was also a pioneer in aerial photography. He piloted a balloon called "The Giant," from which he created panoramic

vistas and aerial viewpoints of the city and the countryside.

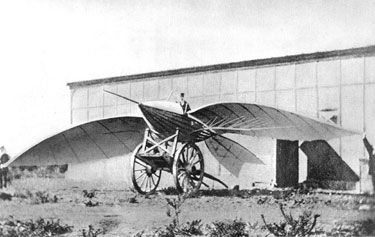

|

Le Bris and His Flying Machine (1868) - Nadar. Nadar was an extremely imaginative person who had a passion for all sorts of flying objects. His photographs comment on the French fascination at the time for new inventions and machines. Nadar communicates the scale of the machine by including a person in the image.

|

In England, Julia Cameron (1815-1879) also worked with photography in a creative manner. Cameron insisted on achieving aesthetic qualities in her portraits. She manipulated techniques in order to achieve effects like blurred edges and dreamy atmospheres. She portrayed many personalities of her time, such as Charles Darwin.

Photojournalists and Purists

In the United States, Thomas Brady (1822-1896) recorded the American Civil War and the important political events of the time. Jacob Riis (1840-1914) and Lewis Hine took pictures that exposed social evils. Riis photographed the slums of New York, and Hine documented the miserable working conditions of the poor, especially the children.

In 1902 Alfred Stieglitz, Edward Steichen, and other American photographers formed a group to promote photography as an independent art form, called the Photo-Secession. They challenged the idea of retouching photographs, and championed pure photography. (I guess they would not be fans of Photoshop today.)

Since then, photography has seen many major developments, from photojournalism to abstractionism, to street photography and studio professionalism. In any case, photography remains an important part of art and

of our popular culture and everyday life.

In Lecture Two, we studied Impressionists and Post-Impressionists who were captivated by the study of nature. Now, let's turn our attention to those of Monet's followers who were concerned about the social phenomena of their time.

Social Life Depicted by Impressionists

Edouard Manet (1832-1883) shocked the French art crowd with his female nudes in his paintings Luncheon on the Grass and Olympia. Both paintings show the female figure in a bold pose, gazing directly at the viewer, emphasized by a severe lighting contrast and flat silhouetted forms.

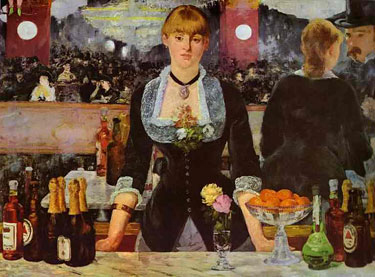

Manet's A Bar at the Folies-Bergere (1881) portrayed Parisian nightlife. With dazzling colors and rich textures, he depicted a bartender gazing out towards the crowd. We can actually see what she sees through the reflection on the bar mirror placed behind her—an animated crowd, smoking, drinking, chatting, and walking around. Manet makes a distinction between the

monotony of serving a bar and the bourgeoisie enjoying leisure time.

|

A Bar at the Folies-Bergere (1814) - Edouard Manet. In Manet's painting the figures reflected in the mirror are blurred, indicating that they are moving around. Manet also uses the formal opposite of blurred edges: the silhouette, a flat, precisely outlined image. The black ribbon around the barmaid's neck, the lightbulbs on the columns, and the golden foil of the champagne bottles are all silhouettes.

|

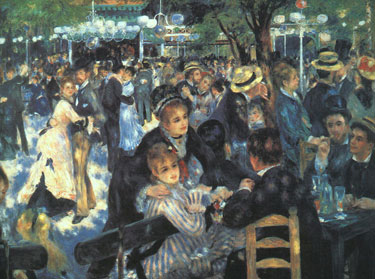

Auguste Renoir's (1814-1919) Dance at Le Moulin de la Galette (1876) is also a portrayal of leisure. We can see a dance hall packed with dancing couples, and people sitting at tables drinking and chatting away. Some couples are cropped by the edges of the painting, giving the impression that the image is a section of a larger scene. This "slice of life" or cropped quality of the viewpoint is a characteristic of Impressionism that can be associated with photography. Renoir's brushstrokes are characteristically soft, with a velvety kind of texture.

|

Dance at Le Moulin de la Galette (1876) - Auguste Renoir. The background is occupied by dancing couples, while in the foreground, a group of men and women converse around a table with their glasses reflecting the light. The strong diagonal of the bench separates the two groups.

|

Edgar Degas (1834-1917) also portrayed situations of modern life, though he emphasized composition, drawing, and form more than the other Impressionists. He is well known for his pastel series of ballerinas, executed in the

late 1870s.

|

The Dance Class (1873-1875) - Edgar Degas. Note how Degas tilts the floor upwards, making us see the figures from a low point of view, as if we were seated in the audience. Also notice the transparent quality of the dancers' tutus, which allows the viewer to perceive the upper parts of their legs.

|

But he also made pictures depicting the psychological isolation that takes place in the big cities. In the Absinthe Drinker (1876), he depicts a drunk woman, slouching in front of a glass with absinthe. In contrast to the movement of his ballerina series, the Absinthe Drinker exudes physical inertia.

Mary Cassatt (1845-1926) was an American painter who spent most of her life in Paris and is credited with introducing Impressionism to American collectors. Cassatt painted scenes of people engaging in ordinary daily activities. She is particularly noted for paintings of peaceful, loving moments shared by mothers and their young children. Cassatt also painted scenes of women drinking tea, quietly reading, or writing letters. My favorite Cassatt painting is Mother About to Wash her Sleepy Child (1893). As a mother myself, I can relate to the image—some things have not changed at all!

|

The Bath (1893) - Mary Cassatt. Cassatt allows us to peep into this intimate moment of everyday life. Like Degas, she depicts her subject from a special point of view, in this case the perspective of someone looking down on the scene.

|

Social Depictions by Post-Impressionists

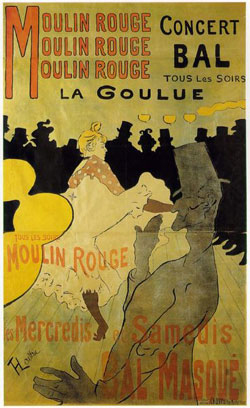

Henri Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901) based most of his characteristic imagery on Parisian nightlife. You might know something about Lautrec through the blockbuster movie Moulin Rouge (with Nicole Kidman and Ewan McGregor).

Toulouse-Lautrec is the midget artist character in the film, always drunk on absinthe. In life, he died of alcoholism at the age of 37. Lautrec designed many posters for the Moulin Rouge, a popular cabaret. Because the purpose of a poster is to advertise events, letters are integrated into the composition. His ability to integrate artistic expressions into a commercial designs still influences many graphic designers today. Among his favorite subjects were dancers, singers, circus performers and prostitutes.

|

Moulin Rouge (1891) - Henri Toulouse-Lautrec. Lautrec's lithograph posters consisted of flat, unmodeled areas of color. Here, he uses the strong black silhouette of the audience to offset the more textured hair and blouse of the dancer.

|

Though now famous, the painter Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890) received very little recognition during his lifetime. He was a complex character who poured his emotions into his paintings. In his last years he painted mostly landscapes and still life images from Arles, a Mediterranean town in the south of France. His most famous pictures from this time are The Starry Night (1889) and Wheat Field and Cypress Trees (1889). His brushstrokes in these images have a dynamic character with the thick texture of oil.

In his younger years as an artist, Van Gogh painted many scenes of peasant life, showing us his intense feeling for the poor. In 1878, he became a preacher in a poor coal-mining district in Belgium. The Potato Eaters (1885) is his best known piece from this early period. He depicts a peasant family enjoying their simple evening meal with the solemn importance of a ritual. Van Gogh also left a lot of self-portraits, which reveal his emotional feelings and state of mind.

|

The Potato Eaters (1885) - Vincent Van Gogh. The dark palette and subject matter of the potato eaters reflect a social consciousness reminiscent of 19th century realism. The bold features of the characters give them the quality of a caricature.

|

Painter Paul Gauguin (1848-1903) produced his most intense work while he was living in Tahiti and the Marquesas Islands, from 1892 until his death. Polynesian life and culture became the entire subject of his work. He saw the islands as a new Eden in which nature took precedence over the corrupt and industrial civilized West.

|

We Shall Not Go to the Market Today (1892) - Paul Gauguin. Gauguin uses bright colors of Tahitian culture to guide our eye through the picture. The women's poses may remind you of Egyptian art.

|

Gauguin was one of the first artists to incorporate non-Western forms and motifs into Western art, expanding the scope of our intellectual and aesthetic experience. In his painting Never More (1897) he uses a native model to depict a recurrent image in art: the female reclining nude.

Futurism was an artistic movement with political implications founded in 1909 by the poet Marinetti. Futurism glorified the so-called "machine age" of modernity in a series of exuberant manifestos. Power, speed, machinery, technology, travel, and violence were among the preferred subjects of the Futurists. They attempted to represent movement in their work by breaking up realistic forms into multiple images and overlapping fragments of color. (We saw this in the last lecture in Umberto Boccioni's sculpture Unique Forms of Continuity Space.)

Futuristic painting and sculpture captured the general feeling at the beginning of the 20th century, when major changes were taking place. Futurism tried to inspire in the general public an enthusiasm for a new artistic language. It tried to abolish academic traditions in all the arts—the visual arts, music, theatre, literature and film. Creative energy was focused on the present and future. Some Futurist painters that are worth studying are Giacomo Balla, Luigi Russolo, Carlo Carra, and Gino Severini.

|

| Dynamic Automobile (1913) - Luigi Russolo. Russolo uses vibrant colors and diagonal shapes to create a feeling of motion and speed in his painting. |

By 1916 Futurism had lost its vigor, but it continued to influence other modern styles such as Dadaism, Expressionism, and Surrealism. Let's discuss one of those -isms now.